North Marsh is - you guessed it - a marsh area on the northern boundary of Askham Bog SSSI. Askham Bog is Yorkshire Wildlife Trust’s oldest nature reserve, founded in 1946 and founding – in turn - Yorkshire Naturalists' (now Wildlife) Trust.

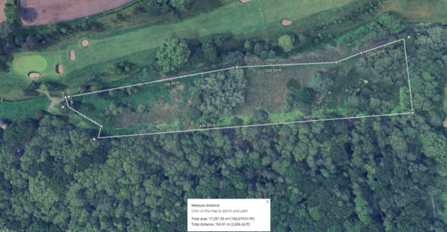

North Marsh is approximately 5 acres in size, a long thin strip which sits between the north side of Far Wood and the main ditch which flows around the Bog. It’s one of those hidden bits that our visitors don’t see; as the reserve is surrounded on three sides by Pike Hills Golf Club, access to North Marsh is across the golf course land and then requires climbing over thick fallen willows, leaping over ditches and battling through nettles, reeds and Himalayan balsam.

Once upon a time, North Marsh was a nice patch of fen meadow, with various wetland species of fern, sedges, wildflowers, orchids and patches of small scrub. However, it sits between Far Wood and the main ditch, and Far Wood is being managed through a zero-management approach to study what happens to wet woodland based on acidic peat.